I am autistic. I was formally assessed a couple of months ago, but I suppose I have known it for most of my life. I am different. Sunny days are blinding for me, I would freak out if you casually popped in for a cup of tea, but I might give you my 2nd kidney if you needed it (I need only one, and they usually fail together). It is not the endearing kind of “different” that is embraced and loved by society, a quirky girl who laughs too loud like Meg Ryan or Joan Cusack, but the kind of different that has made me feel ostracized for most of my life. My way of being is usually labelled as not normal, odd, antisocial, and just generally “wrong”. But there is nothing wrong with me. I am simply neurodivergent and that is alright.

Neurodivergence – what is it?

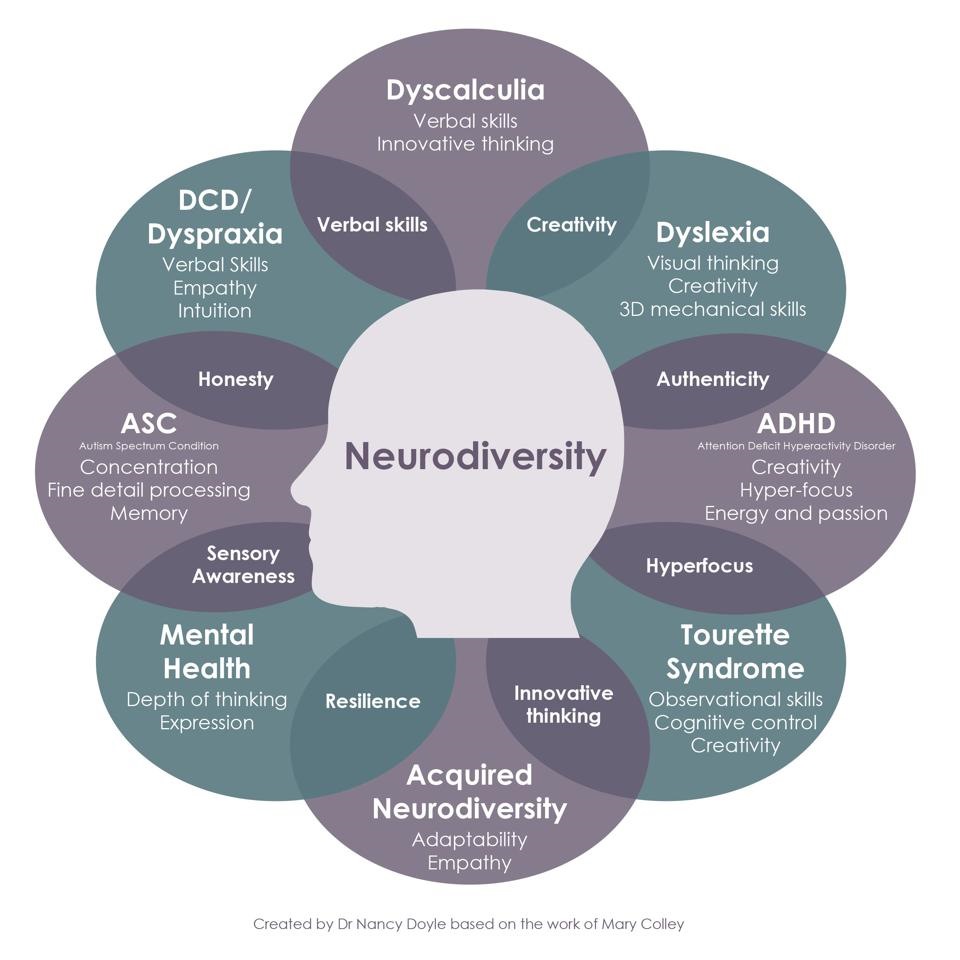

Let me start by explaining a few of the terms. It is worth pointing out that the terminology is still new and not entirely agreed upon. The current thinking is that we live in a neurodiverse society. Neurodiversity is the idea that not everybody perceives and interacts with the world in the same way. This is due to differences in human brain function. Around 1 in 7 people are estimated to be neurodivergent, neurodifferent or neurominorities, which means their brains are wired somewhat differently and they have named conditions, including, but is not limited to, the conditions depicted above. Confusingly, the term neurodiverse is sometimes used to mean neurodivergent.

People who are not neurodivergent are sometimes referred to as “neurotypical”.

In most progressive cultures today, there is a drive towards emphasizing that there is no hierarchy in race, religion, sexual orientation or gender. But until 1972, even in the US, homosexuality was considered a mental illness. That was just 50 years ago! Though there is a long way to go before we reach universal equity in those spaces, today, in liberal cultures, the need for equity has been widely accepted. Most workspaces, school, universities, and governments acknowledge this need. Most people get it.

That isn’t the case with neurodiversity, even in progressive cultures. The terminology itself reveals the underlying perceptions. The negative labels – “dys” and “disorder” – indicate as much. People “suffering” from these “disorders” are perceived to be lesser, needing medical care to “cure” them of their impairments. There is little knowledge and many misconceptions. When we talk of Autism, most imagine a “Rain-man” type genius able to count cards in Las Vegas, having irrational outbursts over pancakes. When we talk of Tourette’s, most imagine a hilariously inappropriate swear word being shouted during a formal black-tie event.

we understand more about the human brain, we are realizing that these conditions are not defects, merely differences. They put neurodivergent people at a disadvantage because we live in a world that caters to neurotypicals. Having an intense interest in science and maths and a decent memory, I did pretty well in school. But back in sunny Sri Lanka, when I was 12, my classroom was moved to a brand-new building in my school. Whitewashed with large open windows, the room was airy and full of sunlight. I could not look up from my desk at the teacher, everything was blindingly bright. I tried to explain, but the teacher dismissed my issue as fussiness. That year I missed about 3 months of school because of headaches. I came 27th in the class of 30. A few years later, by the time I was studying for my GCSEs, we were back in the old gloomy buildings. I went on to get 8 distinctions. Looking back, I wonder how different my life would have been if my GCSE classroom was in the new building.

If we remove sensory and societal barriers, the neurological differences of autism can result in strengths.

The path to equity in neurodiversity is a long one. The good news is that the journey has started. We are learning more about ourselves, defining our identities with neutral language, raising awareness, debunking myths, and fighting for equity.

Autism – are we all on the spectrum?

Short answer, no.

Medically, autism is referred to as ASD, Autism Spectrum Disorder, a rather problematic name. We’ve already touched upon the glaring problem with the word “Disorder”. The autistic community prefer the term ASC, Autism Spectrum Condition.

The word “Spectrum” is also trouble.

The history of autism diagnosis is rife with issues. Autism was first recognized as a condition in 1943 by Dr Kanner. But in 1952, the major American text for psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), referred to it only twice and in relation to schizophrenia, now known to be completely unrelated to autism. In the 1970s, psychiatry underwent a change in emphasis, away from psychoanalytic causes and towards diagnostic effects. This resulted in an effort to define autism via quantifiable diagnostic criteria. By 1980, the DSM recognized autism, but it was only in 1994, when “Asperger’s”, a form of autism seen in people with average or high IQs, was included, that autism started to look like a spectrum. By 2013, the DSM had redefined autism as a spectrum, with high-functioning at one end and low-functioning at the other.

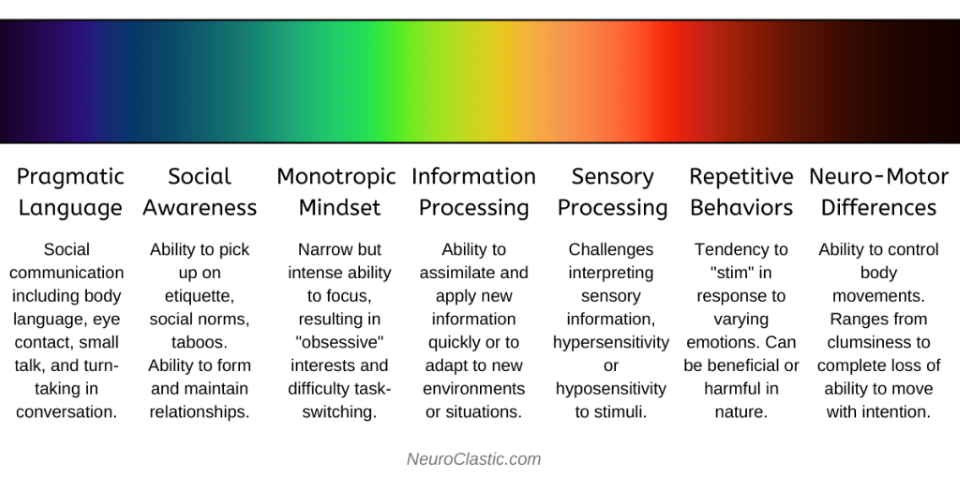

Many do not agree with this way of seeing autism. See, the reason autism is defined as a Spectrum, is because it is a complicated combination of several seemingly different characteristics. No two people with autism are the same. But this does not mean that people are more or less autistic.

In a 2019 article, C.L. Lynch, an autistic fiction author, explains it beautifully.

Most people think of the autistic spectrum as something like this,

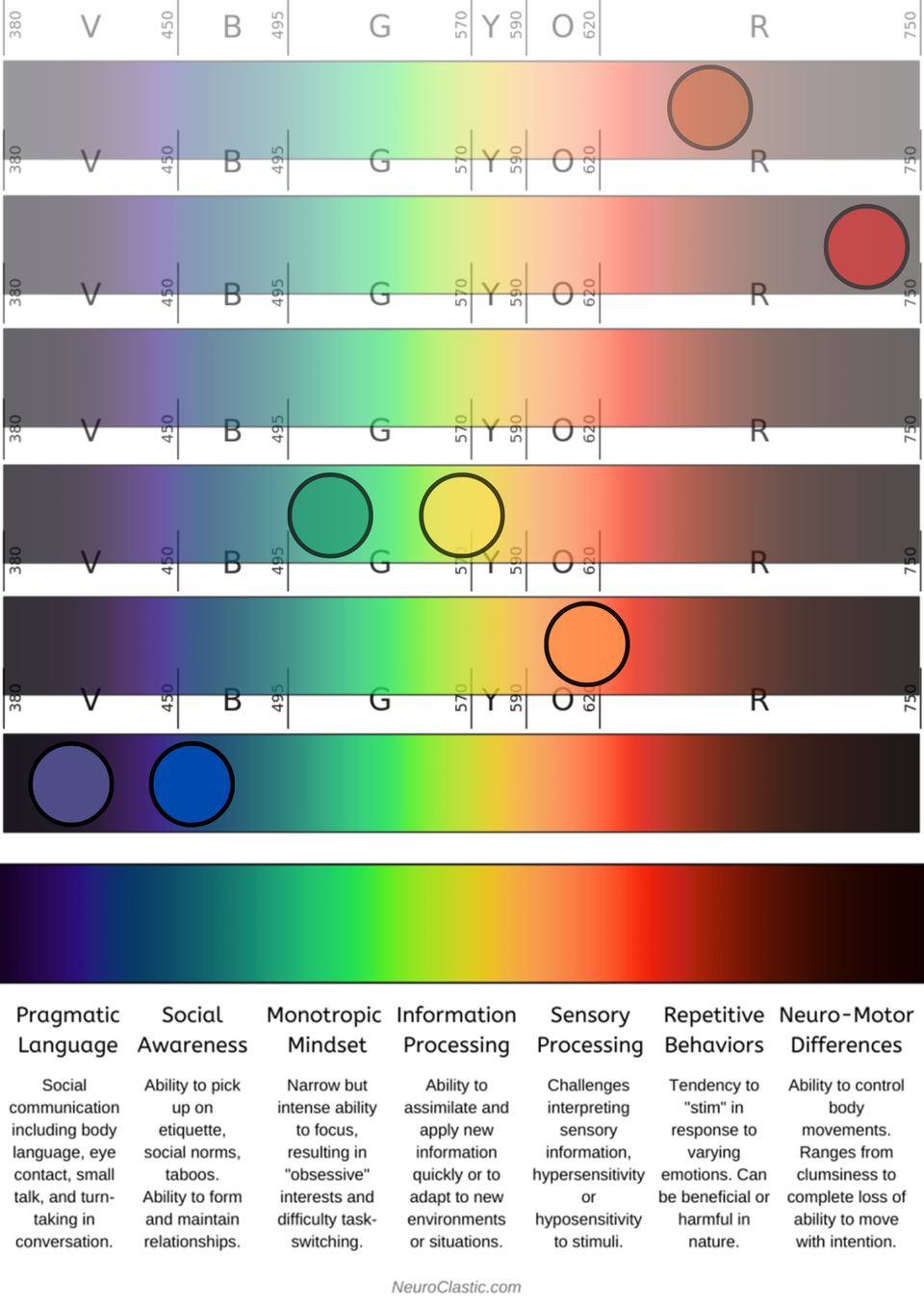

Take the visible spectrum . Even though the wavelengths increase gradually from violet to red, visually, the colours themselves are distinct. Yellow isn’t more blue than red. Yellow is just yellow.

Lynch argues that the autistic spectrum is the same, with distinct characteristics that each autistic person experiences to a different level. To be autistic, you must have difficulties in multiple categories across the spectrum.

Please note that the characteristics below are just a simplified example to illustrate Lynch’s point, not the definitive medical definition of autism.

Taking the visualization further, I see the autistic spectrum as two dimensional, both colour and intensity. I have drawn pretty circles to represent where I feel I sit in this spectrum. Some areas have been a massive struggle for me, others almost not at all.

But you don’t seem autistic!

When I told people I was seeking an autism assessment, the feedback was mixed. Some of my oldest friends were totally surprised, “you don’t seem autistic!” but others, not at all. Interestingly, the people who were surprised were mostly friends from school and work, spaces in which I have had to mask the most.

Autism masking is a social survival strategy, which, to put it bluntly, is pretending to be like a neurotypical in the areas in which you know you aren’t. It is thought that Autism goes undiagnosed in girls more than boys because girls are more likely to mask due to an inclination for friendship.

When I was little, I watched a show where the detective knew the culprit was lying because they avoided eye contact. What was eye contact? Why would people look at each other’s eyes when they spoke? That’s not where the words come out of! See, I looked at people’s mouths when they spoke. I had not even realized this was not typical. After that, I remember teaching myself to make eye contact. Initially it did not make sense. People had two eyes; I could not look at both at the same time! Which one was I meant to look at? I remember picking the bridge of their nose instead. But that could not hold my gaze and my eyes would wander back to their mouths. Finally, I chose the eye to my left and looked at that. It seemed to work. I am 42 years old now and I no longer do this when I speak to people. I make eye contact and I feel it comes naturally to me. But I did have to teach myself how to do this.

It was not only with eye contact. I learned how to small talk by watching my sister talking to others about the weather, traffic, the cold they had last week – and I would see how people responded, smiling, connecting, so I would copy. It did not always work, my conversation came out clunky and disjointed, but over the years I found ways to focus on the masking I was good at and avoid the masking I was bad at.

I learnt to tolerate bad smells by sucking on sweet smelling candy. I learnt to tolerate bright lights by always wearing sunglasses. I learnt to tolerate background noise by wearing earphones. All the while pretending to the world that those smells, lights, and noise did not bother me.

I have done some of the masking for so long as it doesn’t feel like masking anymore – like eye contact. But in other areas, like turn taking in conversation, stopping myself from talking over others is a constant effort. I pretty much have to say to myself, “not yet, not yet… waaaaait”.

On the surface, it doesn’t sound so bad. We all do that, right? Hide our left-wing political views from our right-wing in-laws? Pretend to enjoy eating that dish to make that aunty happy? But imagine doing it all the time and with everyone. It is exhausting. I find that I need a day off, sometimes two, after any social event, to simply recharge my batteries and gather the strength to mask another day. But the negatives of masking are worse than it being tiring. On a very fundamental level, we feel fake, we lose our sense of identity. We feel that people do not accept us for who we are. To be liked, to get into that university, to get that promotion, to be part of that group of friends, to fit in, we must pretend to be someone we are not. Often, masking results in mental health issues like anxiety, and depression.

Neurodivergence in the workplace

Neurodivergence is something a person is born with, and they live with it for their entire lives. Their brain experiences the world differently and as a result they struggle in some areas that neurotypicals do not struggle in – if autistic, perhaps it is eye contact and a sensitivity to loud noises. But they may also excel in other areas – intense focus on the task at hand, amazing memory, or the ability to think outside the box.

The definition of many neurodivergent conditions focuses on the negatives because our understanding of them resulted from a history of illness. A parent doesn’t take their child to the doctors for getting 100% on a math quiz, but they do take them to the doctors if unable to speak by the age of 3. There is also an inherent neurotypical bias in what is thought of as “negative”. For example, being unable to make small talk is only negative in a world where small talk is a prerequisite for social connection. Why should it be?

Some believe that Einstein and Isaac Newton would be autistic if assessed today. Elon Musk has Asperger’s. Richard Branson is dyslexic. Obviously, neurodivergence isn’t all bad for humanity. So why should the world accept neurodivergent people, only if they pretend to be like everybody else when they are not? When pretending this way is so damaging to them?

Neurodivergence has a lot to bring to the workplace. If life at work was made easier for such people, everyone would benefit. The requirements of a job role need to be examined and then the best people for that role should be hired– neurodivergent or not. Then their needs should be accommodated to allow them to excel at their job. For example, accommodating the needs of autistic people in the workplace could be as simple as understanding a greater need for working from home, or a preference for email/text communication instead of face to face. Some roles just may not suit some neurodivergent people. It would be hard to be an effective presales consultant you didn’t use eye contact or practice turn-taking in conversation. That is fine. But if someone interrupts or doesn’t make eye contact during an interview for a programming job, it really should not matter. We have unsaid rules about what we look for in people, what we feel will make them “fit in” to our organizations and be valuable members of the team. But a lot of these unsaid rules are discriminatory towards neurodivergence. We need to reexamine them.

Sometimes, I was so good at masking even I believed it. I told myself I preferred working from home because of my young children. I even convinced myself that my need for dark and quiet solitude after intense social and sensory stimulation was due to migraines.

Getting assessed has been a revelation to me. I feel like I am getting to know myself. I finally feel like it is ok to be me. I don’t have to be like everybody else. There is nothing wrong with me. I am simply neurodivergent and that is alright.

If you feel that you might be neurodivergent, from assessment to support, there are many resources available to help. Not everyone is going to understand. Although it might take decades for people to stop thinking neurodivergent people are “weird” or antisocial”, I’ve found that making people aware of my autism has made them more tolerant. Alas, sometimes patronising and condescending, but generally kinder, more patient. But disclosing your neurodiversity is a decision you can make for yourself, based entirely on what you are comfortable with. Whatever you decide, your neurodiversity is part of what makes you you and embracing it might just help you live your best life!

Written by:

Monalee Wonnacott

Senior Consultant Infor Services, Fortude

Subscribe to our blog to know all the things we do